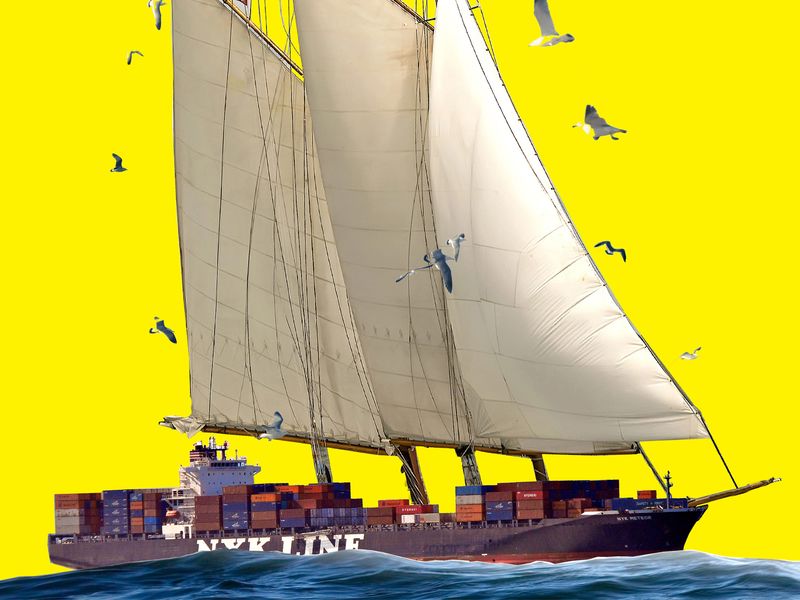

When I was a child, I was riding a sailboat across the ٌRiver Nile to the eastern region of it. These Egyptian boats were led by boys who had strong knowledge of wind directions, wave speed and the movement of the Nile water by instinct. And here is the world today returning to wind energy again to the ancient Egyptian Blooberg confermed that Around 3500 B.C., Egyptian mariners suspended woven reeds on ships to capture wind to propel boats along the Nile River via its report

Ocean transport giants such as Maersk and Cargill have a new take on a very old idea that might help big boats reduce their carbon footprints.

Around 3500 B.C., Egyptian mariners suspended woven reeds on ships to capture wind to propel boats along the Nile River, inventing the first sailboats and enabling maritime commerce. Now modern-day shippers are adapting this ancient technology in a bid to address the very 21st century challenge of greenhouse gas emissions.

Some of the biggest names in the maritime trade are investing in retrofitting or building newly designed vessels that harness wind energy to meet pollution-busting goals and emissions standards. From giant kites that pull cargo ships to inflatable sails to spinning rotors that create lift, the move toward wind-powered commercial vessels will generate a doubling of such ships on the water by 2023.

Although starting from a low base, global shipping giants including Cargill, Maersk Tankers, and Mitsui are tacking into the wind to cut emissions, betting on the revived technology to help meet the industry goal of cutting greenhouse gas emissions from the global fleet by 50% by 2050, from 2008 levels.

By the end of this year, 25 commercial vessels—including seven delivered in 2022—will make use of wind-powered innovations, according to trade group International Windship Association. By the end of 2023, that number will almost double, to 49.

Despite being derailed by the pandemic, a number of high-profile deliveries or orders have taken place in the last 18 months. Airseas, founded by former engineers at aerospace giant Airbus SE, installed a parafoil kite that can be deployed with the push of a button on a Louis Dreyfus Armateurs SAS vessel chartered by Airbus.

The device will cut shipping fuel costs and greenhouse gas emissions by an average of 20%, or as much as 10,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide annually, the company says.

“Shipowners know they have to reduce their emissions now and need to start investing to meet the 2050 goals,” said Lesage. “It makes sense for shipowners to include wind as part of any solution. Wind is abundant, free and it’s an unlimited source of energy.’”

In July, Japanese shipping company Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd. (K Line) boosted its Airseas kite orders to five and signed a contract to install as many as 50 on its fleet of about 420 vessels. Deploying wind propulsion technologies is a “key component of our strategy” to adopt an ambitious net-zero greenhouse gas emissions target by 2050, said Michitomo Iwashita, managing executive officer of K Line, in a news release.

Meanwhile, giant commodity trader Cargill Inc. will pilot-test two 120-foot-high rigid wind sails made of steel and composite glass that will be outfitted on the 751-foot-long carrier that it charters and Mitsubishi Corp. owns.

The vessel is longer than the length of two American football fields. Sails could help cut emissions on a new-build ship optimized for wind by as much as 30%, which equates to about 6,400 metric tons of carbon dioxide per year, according to Cargill.

It plans for the ship to operate commercial runs for up to six months after it’s delivered in the first quarter of 2023. If the trial is successful, Cargill plans to retrofit as many as 10 more ships, says Jan Dieleman, president of Cargill’s ocean transportation business.

“Decarbonization is a very big piece for us. It’s the biggest challenge the industry is facing,” Dieleman says. “If you really want to make a step change you need to get to wind and zero-emission fuels. That’s very much the work we’re on.”

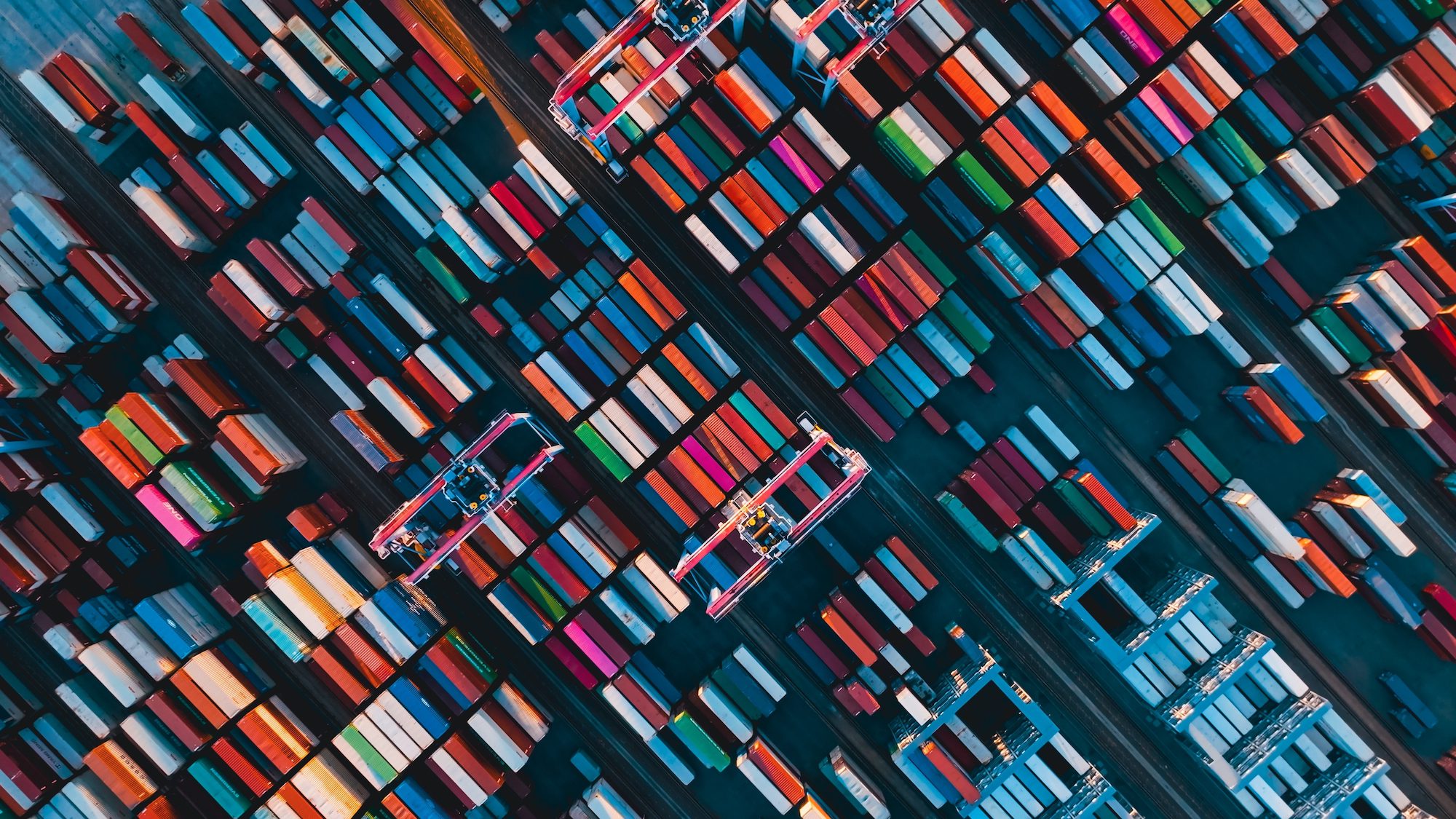

Shipping transports 90% of world trade and accounts for 3% of global greenhouse emissions, or about 1 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide a year. The International Maritime Organization, the United Nations agency that regulates air pollution from shipping, has adopted mandatory measures to reduce greenhouse gases. Starting on Jan. 1, vessels over 400 gross tons must meet certain energy efficiencies, and most shipowners will need to implement technical measures so their emissions comply with the required levels. Vessels will need to meet that standard to continue trading globally.

With the focus on drastically cutting emissions, the shipping industry will likely face a transformation over the next several decades that’s as dramatic a disruption as the one it faced at the end of the 19th century, when commercial ships propelled by wind and sails quickly lost favor as the Industrial Revolution ushered in the diesel engine.

In 2014, when the International Windship Association was formed, shipowners would laugh or walk out of the room when the group’s secretary, Gavin Allwright, brought up wind energy for commercial vessels. Now, he says, shipowners line up to get the latest on wind news when he fields calls several times a week about the technology.

There are about 12 wind propulsion systems on the market, with as many as seven more coming online in 2023, Allwright says. Several companies, including Norsepower Oy in Helsinki, offer rotor sails—one of the more developed innovations, since the rotors have been around since the 1920s. The large, round cylinders can be as tall as 35 meters and spin to create a pressure differential that propels the vessel forward.

BAR Technologies, which designed the 37.5-meter rigid sails that will be installed on Cargill’s chartered ship, and others are competing to install multiple sails on vessels. Michelin, the tire company, will install a 100-square-meter (1,076-sq-ft) inflatable and retractable automated wing sail on a container ship for a trial later this year, it says. Netherlands-based Econowind BV is installing its Ventifoil wing-shaped device, which creates suction that generates thrust for a ship, on two cargo vessels this year. Others are developing a sail that can be put in a container after use and easily moved around to other ships.

The current beehive of activity is spurred by record fuel prices, ambitious global emissions targets, and the reality that clean, green fuels for ocean vessels will take years to be developed—and be very expensive when they come to market. Zero-emission fuels such as green hydrogen, methanol, and ammonia—cornerstones of the industry’s decarbonization plans—aren’t likely to be available for shippers to use widely until after 2030, when they’ll also need to compete for supplies with other industries looking to go green, says Cargill’s Dieleman.