London. UK. / Auckland. New Zealand. At 4 am on June 20, 2011, the entire Indonesian crew (32) walked off the Oyang 75 when it berthed in Port Lyttleton, Christchurch. This was the first time, anywhere in the world, an entire crew had walked off a South Korean factory trawler. They had been fishing at sea for only five weeks, on its first outing in New Zealand waters, yet already the crew had had enough of the abuses they had suffered by Korean officers within that short time period.

On that same June day, I was contacted by Daren Coulston to come down to Christchurch and bring my camera equipment. The previous year, Daren and I had traveled to Indonesia to investigate the August sinking of the Oyang 70 in New Zealand waters, with the loss of five Indonesian crewmen. That unnecessary sinking had happened because of the greed of the captain by bringing on board an overweight bag of fish that caused the Oyang 70 to capsize.

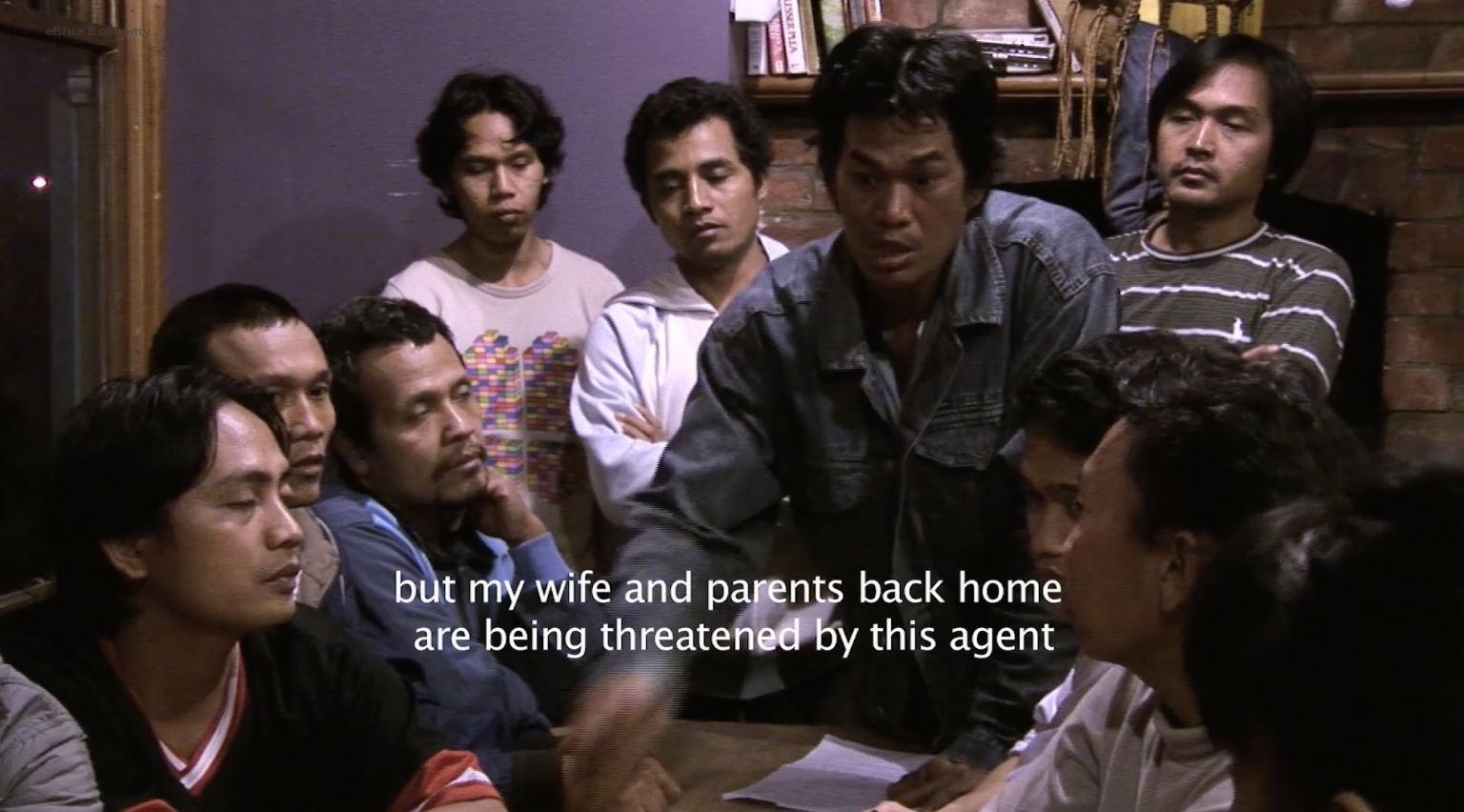

For the next 3 weeks, I stayed with the Oyang 75 crew, who had taken over a backpackers hostel and filmed interviews with them and what was happening to them and their families in Indonesia. Helping Daren look after the crew was local Indonesians Elyana Theau and Dr. Nurani Kartikasari, and they both agreed to conduct interviews for me.

Because of the trust, the crew put in these three, they spoke freely, and soon the appalling treatments this crew suffered were revealed. I was shocked that such abuses were happening in my country which was one of a small number of countries that had successfully lobbied for human rights to be included in the United Nations 1945 Charter, which led to the Universal Declaration on Human Rights being adopted in 1948.

Being hit by their officers was a daily occurrence, and it became obvious that not one crewman escaped such abuse. They were often forced to work continuously for two days, harvesting and processing with only 3 hours for sleep, resulting in tiredness, therefore, mistakes therefore more beatings. Sexual abuse by officers was also common; this brought great shame to the men. Over my various filming trips, it became obvious that this abuse was not uncommon on many South Korean vessels.

The crew was soon being subjected to immense pressure from Sajo Oyang Corporation’s New Zealand representatives to return to their vessel. Adding to that pressure, their families back in Central Java were getting phone calls from the crews’ manning agents, as well as visits by police officers paid by these agents, threatening them with losing their homes or land that had been used as collateral for their men’s contracts. Also, most of the crew had borrowed large amounts of money, usually from relatives, to pay for various expenses traveling to Jakarta, as well as agents’ fees to get a job.

They would often have to make several trips and wait for 6-8 months before a job was found. At one stage, families were being told that if the crew didn’t return to their vessel the families would have to pay a US$1000 cash penalty, an impossible amount for them to find, let alone afford, as, for many families, that represented close to their local annual income. After all, as Central Java has high unemployment, this was why these men took these jobs; feeding their families and paying for their children’s education being their primary reason.

Encouraged by the Oyang 75 crew’s audacity, other Indonesian crews started speaking to us about the abuses they suffered daily on their Korean factory trawlers working in New Zealand, and this suffering was clearly widespread throughout the fleet.

Several mentioned that these abuses were common on other Korean factory trawlers working in global waters, so, asking Dr. Kartikasari to be my co-producer and fixer, over the next few years we made several trips to Central Java to record this global abuse and film local conditions to explain why these men took these jobs.

Hearing about these abuses was even more shocking than those that occurred in New Zealand.