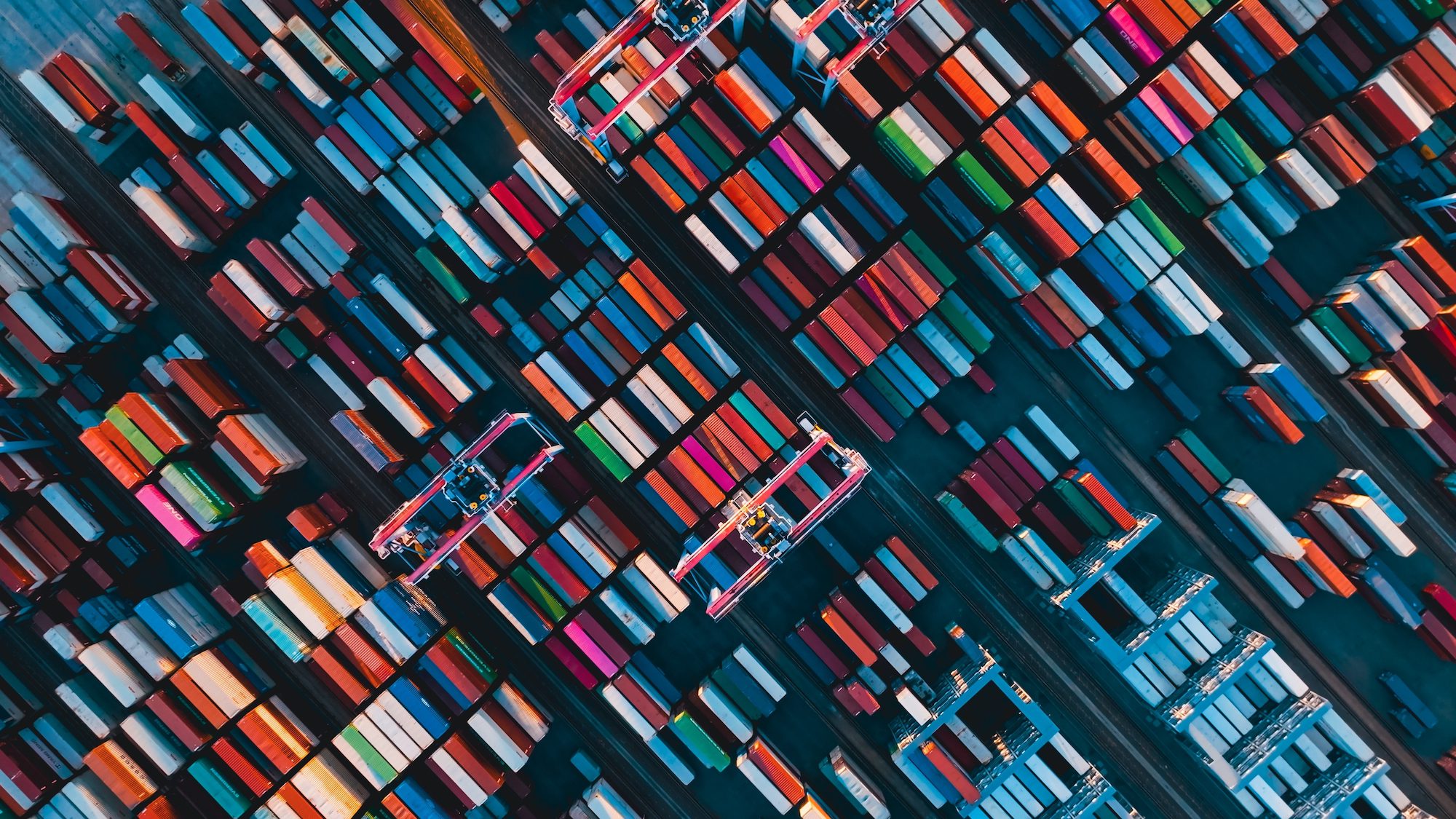

ORF: For centuries, oceans—covering more than 70 percent of our planet—have been and still continue to be a major source of food, energy, and livelihoods.

Today, no part of it remains unaffected by human influence, clearly underscoring the need for enhanced maritime governance to address the threats characterizing the maritime space including, but not limited to, illegal and unreported fishing, unsustainable and destructive fishing practices, habitat destruction, the introduction of invasive species, ocean noise, pollution from both land-based and ship-based sources, ship strikes (collisions between marine life and vessels), the extraction of oil and gas, and the mining of minerals.

These, in turn, lead to shifting currents, ocean warming, ocean acidification, and decreasing oxygen levels. All of these impact marine life, and with the significant rise in human activities, threats to the ocean space have also compounded.

The sustainable exploitation of ocean reserves is an essential requirement to safeguard the planet’s waters from being ravaged by climate change, unchecked human impact pollution, and environmental degradation. While marine resources such as fish stocks are crucial for the lives and livelihoods of coastal communities, the maritime expanse creates scope for a number of non-traditional security threats as mentioned earlier.

Maritime security does not merely comprise geopolitical imperatives arising due to the securitization of the seas but rather encompasses a vast gamut of areas concerning human-induced interventions resulting in adverse socio-economic impacts. The establishment of practices that are geared towards this particular aspect of maritime security is exactly why the issue of maritime security must be linked with maritime governance—to create informed measures for global action.

The link between maritime security and maritime governance stems from the fact that the adoption of effective maritime security measures by individual countries is directly related to the establishment of maritime governance.

As global commons, oceans require considered and concerted efforts of all countries. Of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), SDG 14, in particular, relates to the conservation and sustainable use of oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development and hence links directly with sustainable efforts towards maritime governance. The recognition of oceans as a standalone goal by SDG 14 also allows a bridge between the 2030 Agenda and the UNFCC process.

In order to make SDG 14 actionable, the United Nations has sought the participation of “all stakeholders” through “innovative new partnerships” via the achievement of 10 targets and 10 indicators. These targets include sustainable fishing, protection and restoration of ecosystems, reduction of marine pollution, and the increase in economic benefits for using sustainable fishing practices, to name a few.

The link between maritime security and maritime governance stems from the fact that the adoption of effective maritime security measures by individual countries is directly related to the establishment of maritime governance. This, in turn, can help in the advancement of development cooperation and sustainable utilization of marine resources via partnerships for advancing economic development, raising public awareness, periodic tracking of actionable objectives, increasing policy-level discussions and interventions through the participation of relevant stakeholders, and the sharing of information and best practices on maritime governance.

Additionally, this also links with the development of the blue economy, which concerns not only marine offshore areas but also coastal communities and resources. States should, therefore, be encouraged to invest in building and acquiring tools for the development of the blue economy as an extension of their efforts at improving maritime security. First and foremost, amongst these measures, however, is the acknowledgment that the lack of or inadequate maritime safety measures impacts all nations and all peoples.

At the same time, however, a key challenge with respect to all forms of international cooperation—marine governance being no exception—is that of enforcement. This is why the governance of marine areas beyond national jurisdiction becomes more intractable.

The work of the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) is vital in realizing the goals of SDG 14 as, amongst other aspects, the IMO is accountable for the betterment of safety and security of international shipping (vessel construction, design, equipment, operation, manning, and disposal), and the prevention of pollution from ship movements—both of which are important for SDG 14. Because the bulk of global commerce is reliant on the use of maritime routes, the IMO plays a significant role in ensuring that maritime vessel movements do not upset the marine environment and remain energy efficient.

For the protection of maritime wildlife, the mandate of the IMO also covers the reduction of underwater noise from ships, a blanket ban on the discharge of harmful wastes and litter from ships, and the adoption of measures to avoid collisions between vessels and marine mammals. In addition to these broad initiatives, coastal management also forms an unassailable element for the management and regulation of fishing practices. SDG 14 comprises the backbone of marine governance and environmental security as the realization of 38 percent of all SDG targets is contingent upon ocean sustainability. The importance of SDG 14 in the mitigation of traditional as well as non-traditional security threats cannot be exaggerated.

At the same time, however, a key challenge with respect to all forms of international cooperation—marine governance being no exception—is that of enforcement. This is why the governance of marine areas beyond national jurisdiction becomes more intractable. Additionally, the lack of adequate scientific and analytical tools to inform inter-sectoral approaches such as an ecosystems approach creates challenges with respect to the mitigation of issues in silos. Approaches to improve maritime security would, thus, perhaps be mired in short-term methods rather than the long-term goal of enhancing maritime governance. Mechanisms such as the UNCLOS and various initiatives undertaken by the IMO, to name a few, would thus remain limited in terms of execution in the absence of a holistic vision and a whole-of-society approach.

Source: Observer Research Foundation