By : Nadir Mumtaz (Maritime Analyst)

In the last two decades there has been a tremendous development in maritime logistics, shipping and trade accompanied by advancement in technology , concern about exploitation of oceanic resources and a massive increase in the tonnage of sea going vessels.

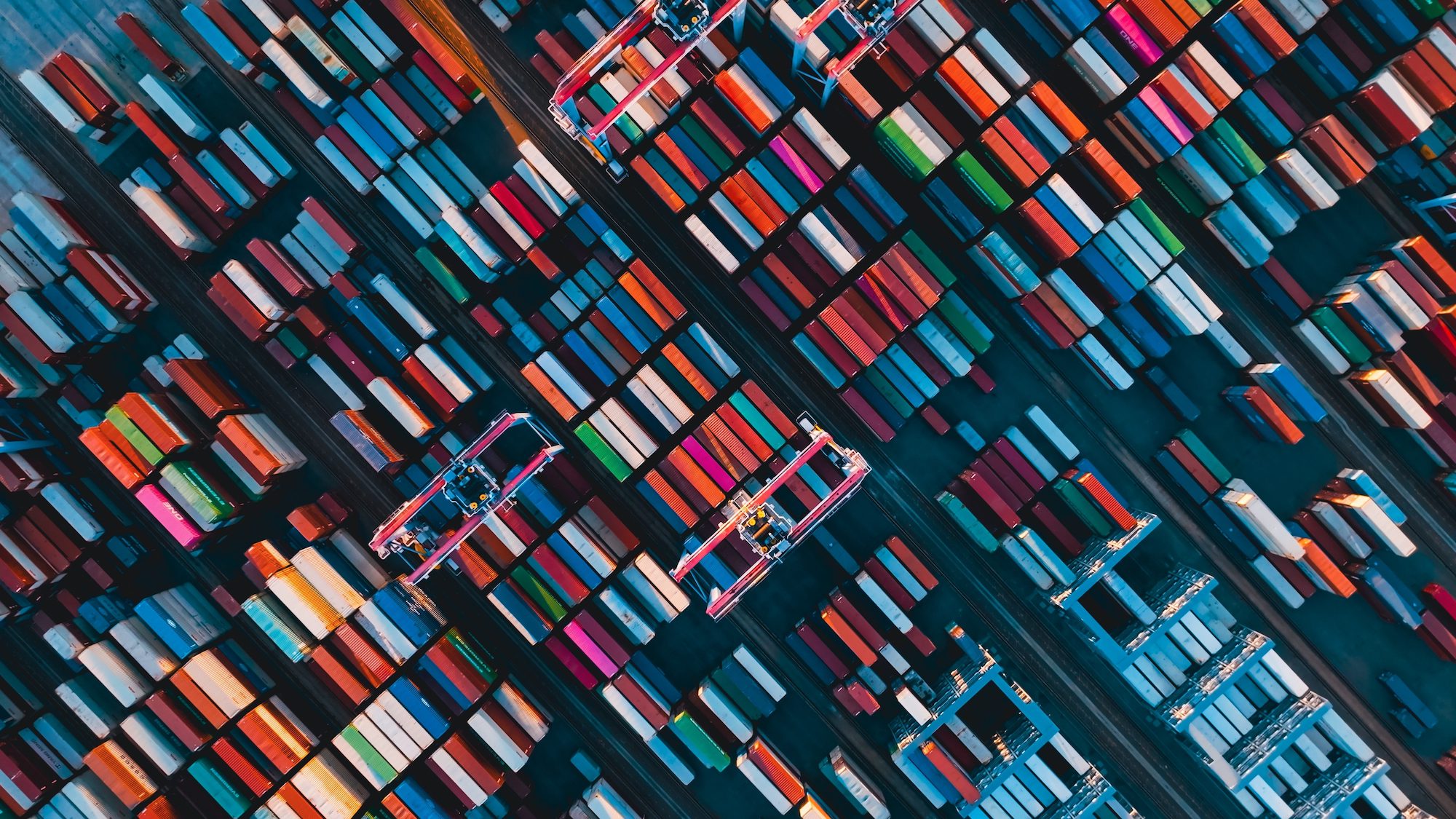

Almost 80 % of global trade is through sea and the developing countries make up a high percentage. Approximately one third of global maritime trade , numbering around 40,000 vessels annually , passes through the South China Sea.

On account of this rapidly changing maritime scenario the term maritime boundaries has at times become interchangeable with maritime jurisdiction or maritime space at times blurring maritime states rights , obligations and responsibilities.

Demarcating maritime territories is becoming complex for various reasons not restricted to pure sovereignty and revenue generation.

With enormous volumes of shipping maritime disputes and disagreements arise mostly to the extent of territorial waters emphasizing that there is an emerging need for crisis resolution

The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) establishes a comprehensive regime of law in the world’s oceans and high seas prescribing regulations overseeing use of the oceans and maritime resources.

UNCLOS is a codification of most of the existing customary international maritime law and provides a legal framework that is being filled in and complemented by existing and subsequently enacted international agreements and its progressive development .

In the context of international shipping UNCLOS stipulates the rights and obligations of the States parties in different maritime zones that need to be adhered to through implementation mechanisms under the umbrella of the International Maritime Organization. China and Russia have signed the Convention however USA has not ratified.

The Convention in Part I provides :

Article 2

The sovereignty of a coastal State extends, beyond its land territory and internal waters and, in the case of an archipelagic State, its archipelagic waters, to an adjacent belt of sea, described as the territorial sea.

Section 2. Limits of the Territorial Sea

Article 3

Every State has the right to establish the breadth of its territorial sea up to a limit not exceeding 12 nautical miles, measured from baselines determined in accordance with this Convention.

Part VII of the Convention describes the freedom of the high seas , reproduced under ;

1. The high seas are open to all States, whether coastal or land locked. Freedom of the high seas is exercised under the conditions laid down by this Convention and by other rules of international law. It comprises, inter alia, both for coastal and land-locked States:

(a) freedom of navigation;

(b) freedom of overflight;

(c) freedom to lay submarine cables and pipelines, subject to Part VI;

(d) freedom to construct artificial islands and other installations permitted under international law, subject to Part VI;

(e) freedom of fishing, subject to the conditions laid down in section 2;

(f ) freedom of scientific research, subject to Parts VI and XIII.

2. These freedoms shall be exercised by all States with due regard for the interests of other States in their exercise of the freedom of the high seas, and also with due regard for the rights under this Convention with respect to activities in the Area.

Article 298

Optional exceptions to applicability of section 2

1. When signing, ratifying or acceding to this Convention or at any time thereafter, a State may, without prejudice to the obligations arising under section 1, declare in writing that it does not accept any one or more of the procedures provided for

Article 311

Relation to other conventions and international agreements

1. This Convention shall prevail, as between States Parties, over the Geneva Conventions on the Law of the Sea of 29 April 1958.

2. This Convention shall not alter the rights and obligations of States Parties which arise from other agreements compatible with this Convention and which do not affect the enjoyment by other States Parties of their rights or the performance of their obligations under this Convention.

It has been witnessed that in the event of a dispute of title or where title cannot be convincingly proven to the satisfaction of one of the parties and parties are at divergence over title then either of the states has opted for the fundamental principle of ‘unity’ to establish its claim of sovereignty over an island .

China’s maritime disputes are centering around maritime sovereignty and resources including Senkaku/Diaoyu islands northeast of Taiwan as well as the intricate mesh with Vietnam, Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, and Taiwan over islands, atolls, reefs, and shoals in the South China Sea.

Threat to China’s maritime security is worrisome for it due to incursion by Western Navies inside China’s Exclusive Economic Zone and perhaps its reaction is manifested in an emerging Chinese capability and resolve to challenge certain elements of such incursions through the deployment of anti-access or area-denial type weapons systems along China’s maritime fringes.

China is apprehensive to threats in what it perceives as its maritime domain and has worked assiduously on strengthening its maritime security derived in part from China’s expanding economic influence .

Despite a culture of restrictions on digital social media the Chinese public opinion reacts strongly to even insignificant or trifling challenges against its maritime sovereignty which in turn mounts pressure upon the government to assert itself. Overall the intensifying maritime sovereignty is underlined by maritime states to realize the potential resource advantages including hydrocarbon and marine resources in what is perceived as an integral part of its maritime area.

Assertiveness of China in the East and South China Seas

China’s assertiveness in the East and South China Seas is in part a response to the perceived aggressive inflammatory and provocative rhetoric by Vietnam, Philippines, Japan, Taiwan in the realm of exploration of oceanic as well as energy resources .

China resolutely and consistently pursues its fundamental policy of supporting regional peace and marine related development yet wherever it feels threatened in the seas surrounding its coast it resorts to jingoism and display of maritime defense capability in what it perceives as its backwaters yet it distinguishes and adopts a civilian or military approach in handling territorial disputes at times studiously avoiding involvement of PLA Navy and it being embroiled in any maritime disputes.

This is evident by it astutely deploying various non-military naval ships and aircraft under the operational control of its organizations namely Border Control Departments such as China Maritime Police, Maritime Safety Administration and Fisheries Law Enforcement Command with some vessels being armed or comprising of decommissioned warships with modified weaponry .

Such vessels are regularly deployed for patrolling , escorting fishing fleets and where need arises responding in a measured manner to threats or violations of claimed territories , islands and waters under Chinese sovereignty. In case of any escalation in local hostilities the implied threat of PLA Naval vessels looms in the distance.

Combining Diplomacy with Display of Authority

In the last fifteen years China has taken certain actions like the dismantling of seismic towed arrays by oil and gas exploration entities, assuming control of land features of Scarborough Shoal and undertaking consistent forays into waters of the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu islands and quarantining fruits from Philippines when Philippines maritime administration detained Chinese fishermen .

As far back as in the year 2012 China’s premier oil and gas exploration company CNOOC laid claim to new blocks in disputed areas of the South China Sea which was understood to be a measured response to Vietnamese movements by flying planes with military markings over Chinese airspace in the South China Sea.

In the East China Sea conflict China expressed its concerns through demarches and avoided any provocative acts in response to Japan’s unilateral act of amending the sovereignty status of Senkaku/Diaoyu islands which it reportedly acquired from private owners while remaining cognizant of Japan’s close military backing and economic links with the US.

The Chinese combine diplomacy with altering degrees of military threat in different maritime zones and traffic corridors carrying goods to Western and Eastern destinations.

US disputes China’s Maritime Claims

The US has been conducting , since the year 2020 Freedom of Navigation Operations which China consistently decries as what it terms and interprets as “ blatant incursions in its territorial waters “ .

Despite the desire and policy of U.S. containment of China both powers need to exercise restrain and maintain a strategic relationship and any minor maritime incident or action should not be misconstrued as acts of aggression by policy makers on both sides and excessive rhetoric may make either of the powers reluctant to retreat from any avowed position adopted thereby risking the security of international maritime shipping lanes in the South China Sea .

Ultimately, these disputes are revolving around the theme of Asian nationalism , traditional reminiscences and sentiments, not geostrategy, which notions should instill considerable prudence among U.S. executive authorities . UNCLOS is a fairly comprehensive framework to settle maritime disputes between states. Between the years 2013 and 2015 China commenced extensive land reclamation in the Spratly Island chain in the South China Sea (approximately 200 islands ) creating over 3,200 acres of artificial landforms on seven sites under the Chinese umbrella and built military infrastructure

. In the year 2018 China deployed sophisticated anti-ship , anti-aircraft missile systems and military jamming equipment which was akin to throwing the gauntlet at the US . In the year 2013, the Philippines sought arbitration under UNCLOS over Spratly Island.

In July 2016, an UNCLOS constituted arbitral tribunal ruled that China’s claim over the land features had “no legal basis and China had carried out reclamation within Philippines EEZ.”

The US , which has not ratified UNCLOS, typically asked China to abide by the arbitration tribunal ruling which China considers “ null and void “. China boycotted the arbitration tribunal proceedings as it maintains the position that the tribunal has no jurisdiction as sovereignty of reefs , rocks and islands in the South China Sea cannot be determined by the tribunal.

Analysis of Jurisdiction of UNCLOS Tribunals

There is a view that UNCLOS has been drafted to ensure the interests of countries with large coastlines , sizeable archipelago and erstwhile colonial states which had in the imperialist past annexed large tracts of lands and scattered islands .

Strangely uninhabited islands are entitled to claim a 200 nm EEZ. What remains intriguing is that under the framework of UNCLOS New Zealand , having a population of around five million , possesses 4 million sq km and on the other hand China with a population crossing 1.3 billion has approximately 900,000 sq km.

China’s consistent approach remains that the four major island groups in the South China Sea namely the Spratly Islands, Paracel Islands, Pratas Islands and the Macclesfield Bank area belong to it under the UNCLOS as the waters between these islands are its internal waters on the same pattern as an archipelago state.

China did not participate in the arbitration process insisting that disputes are to be resolved bilaterally through the framework of ASEAN and this viewpoint is strengthened by a cursory reading of Article 298 (1)(iii) of UNCLOS regarding optional exclusions to section 2. China emphasizes that the jurisdiction of UNCLOS is maritime and not about land and it has yet to be determined to whom these land features belong to.

China’s official position is that UNCLOS cannot be the sole basis for determining maritime rights because territorial sovereignty disputes involve general rules and norms.

A dispute over how to interpret UNCLOS lies at the heart of tensions between China and the United States over the activities of U.S. military vessels and planes in and over the South China Sea and other waters off China’s coast.

The United States and most other countries interpret UNCLOS as giving coastal states the right to regulate economic activities within their Exclusive Economic Zones only whereas China’s viewpoint is that UNCLOS permits it to regulate both economic activity and foreign militaries’ navigation and overflight through their EEZs.

China has not accepted the ruling of the arbitration tribunal on jurisdictional basis and places reliance upon the optional exceptions to the applicability of section 2 of UNCLOS . Historical assertions involving bays or titles are covered under Article 298 of UNCLOS.

Any unilateral initiation of compulsory arbitration has to satisfy UNCLOS preconditions and this is clearly not the case here .

The award by the Arbitral Tribunal lost sight of the fact that the issue is primarily a core maritime delimitation and any processing of any such application by the Arbitral Tribunal involves prior and exhaustive input by legal and technical experts and adducing of evidence by all parties to the dispute.

The Arbitral Tribunal interpreted the various articles of the Convention arbitrarily without appreciating the viewpoint of China on the issue of compatibility of the provisions of UNCLOS with existing bilateral and multilateral agreements or arrangements having acquired the force of law.

As far back as in the year 2006 China professed its position that it would exclude “disputes concerning maritime delimitation” from compulsory arbitration, invoking Articles 279, 280, 282 , 298 and 311 of UNCLOS.

In this backdrop the littoral states in the South China Sea , in their peculiar maritime environment , may consider evolving bilateral or multilateral mechanisms to resolve maritime issues in the South China Sea through negotiated settlement to the exclusion of the US.

China’s position appears to be that as a sovereign state it has the inherent right under international law to determine the manner , mechanism and procedure as to how to settle maritime disputes.

Any disagreement over the sovereignty of islands and reefs in the South China Sea involving maritime delimitation remains a territorial issue and out of the scope of the Convention on the Law of the Sea until and unless the relevant states to the dispute otherwise decide .