Some of the most important features of shipping and maritime transport operations for the year 2020 as monitored by UNCTAD

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has underscored the global interdependency of nations and set in motion new trends that will reshape the maritime transport landscape. The sector is at a pivotal moment facing not only immediate concerns resulting from the pandemic but also longer-term considerations, ranging from shifts in supply-chain design and globalization patterns to changes in consumption and spending habits, a growing focus on risk assessment and resilience-building, as well as a heightened global sustainability and low-carbon agenda.

The sector is also dealing with the knock-on effects of growing trade protectionism and inward-looking policies. The pandemic has brought to the fore the importance of maritime transport as an essential sector for the continued delivery of critical supplies and global trade in time of crisis, during the recovery stage and when resuming normality.

Many, including UNCTAD and other international bodies, issued recommendations and guidance emphasizing the need to ensure business continuity in the sector, while protecting port workers and seafarers from the pandemic. They underscored the need for ships to meet international requirements, including sanitary restrictions, and for ports to remain open for shipping and intermodal transport operations.

additional tariffs are estimated to have cut maritime trade by 0.5 per cent in 2019, with the overall impact being mitigated by increased trading opportunities in alternative markets.

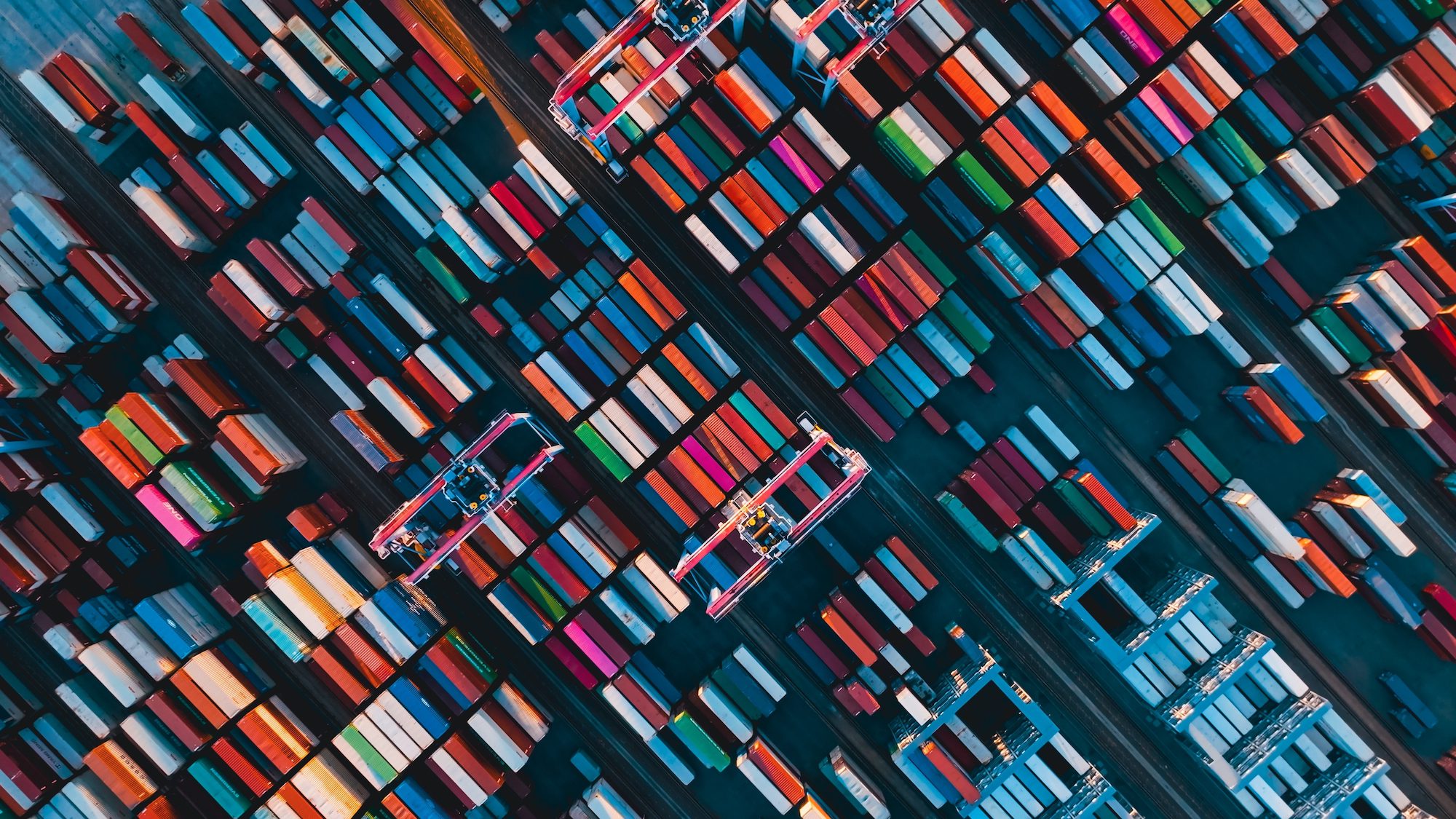

Increased supply capacity remains a concern for the container shipping industry

At the beginning of 2020, the total world fleet amounted to 98,140 commercial ships of 100 gross tons and above, equivalent to a capacity of 2.06 billion dwt.

In 2019, the global commercial shipping fleet grew by 4.1 per cent, representing the highest growth rate since 2014, but still below levels observed during the 2004–2012 period. Gas carriers experienced the fasted growth, followed by oil tankers, bulk carriers and container ships.

The size of the largest container vessel in terms of capacity went up by 10.9 per cent. The largest container ships are now as big as the largest oil tankers and bigger than the largest dry bulk and cruise ships. Experience from other ship types and limitations affecting access channels, port infrastructure and shipyards, suggest that container ship sizes have probably reached a peak.

International maritime trade under severe pressure

The global health and economic crisis triggered by the pandemic has upended the landscape for maritime transport and trade and significantly affected growth prospects. UNCTAD projects the volume of international maritime trade to fall by 4.1 per cent in 2020. Amid supply-chain disruptions, demand contractions and global economic uncertainty caused by the pandemic, the global economy was severely affected by a twin supply and demand shock.

These trends unfolded against the backdrop of an already weaker 2019 that saw international maritime trade lose further momentum. Lingering trade tensions and high policy uncertainty undermined growth in global economic output and merchandise trade. Volumes expanded by 0.5 per cent in 2019, down from 2.8 per cent in 2018, and reached 11.08 billion tons in 2019. In tandem, global container port traffic decelerated to 2 per cent growth, down from 5.1 per cent in 2018. Trade tensions caused trade patterns to shift, as the search for alternative markets and suppliers resulted in a redirection of flows away from China towards other markets, especially in South-East Asian countries. The United States of America increased its merchandise exports to the rest of the world, which helped to somewhat offset its reduced exports to China. New

additional tariffs are estimated to have cut maritime trade by 0.5 per cent in 2019, with the overall impact being mitigated by increased trading opportunities in alternative markets.

Total world fleet amounted to 98,140 commercial ships of 100 gross tons and above, equivalent to a capacity of 2.06 billion dwt. In 2019

Increased supply capacity remains a concern for the container shipping industry At the beginning of 2020, the total world fleet amounted to 98,140 commercial ships of 100 gross tons and above, equivalent to a capacity of 2.06 billion dwt.

In 2019, the global commercial shipping fleet grew by 4.1 per cent, representing the highest growth rate since 2014, but still below levels observed during the 2004–2012 period. Gas carriers experienced the fasted growth, followed by oil tankers, bulk carriers and container ships.

The size of the largest container vessel in terms of capacity went up by 10.9 per cent. The largest container ships are now as big as the largest oil tankers and bigger than the largest dry bulk and cruise ships. Experience from other ship types and limitations affecting access channels, port infrastructure and shipyards, suggest that container ship sizes have probably reached a peak.

Economies of scale primarily of benefit to shipping carriers

Larger ports, with more ship calls and bigger vessels, also report better performance and connectivity indicators. Increasing the number of calls by 1 per cent in container ports for example, is associated with a decrease of the time a ship spends in port per container by 0.18 per cent.

Similarly, increasing the average vessel size of port calls by 1 per cent decreases the time a ship spends in port per container by 0.52 per cent. Gains from the economies of scale resulting from the deployment of larger vessels do not necessarily benefit ports and inland transport service providers, as they often increase total transport costs across the logistics chain. A rise in the average call or ship size often leads to peak demand for trucks, yard space and intermodal connections, as well as additional investment requirements for dredging and bigger cranes.

The concentration of cargo in bigger ships and fewer ports often implies business for a smaller number of companies. The cost savings made on the seaside are not always passed on to clients in the form of lower freight rates. This is more evident in markets such as small island developing States, where only few service providers are in operation. These additional costs will have to be borne by shippers, ports and inland transport providers. Thus, economies of scale arising from the deployment of larger vessels accrue mainly to carriers.

Positive performance of freight rates despite the pandemic

As structural container shipping market imbalances remained a concern, liner shipping carriers closely monitored and adjusted ship supply capacity to match the lower demand levels in 2020. Suppressed demand forced container shipping companies to adopt more stringent strategies to manage capacity and reduce costs. Carriers started to significantly reduce capacity in the second quarter of 2020.

Capacity management strategies such as suspending services, blanking scheduled sailings and re-routing vessels have all been used. From the perspective of shippers, service cuts and reduced supply capacity meant space limitations to transport goods and delays in delivery dates, affecting supply chains. In the first half of 2020, freight rates were higher compared with 2019 for most routes, with reported profits of many carriers exceeding 2019 levels.

While keeping freight rates at levels that ensure economic viability for the sector may have been justified as a crisis-mitigation strategy, sustained cuts in ship supply capacity for longer periods and during the recovery phase will be problematic for maritime transport and trade, including shippers and ports.

Seafarers and international cooperation:

Essential and criticalDue to restrictions relating to the outbreak of COVID-19, large numbers of seafarers had their service extended on board ships after many months at sea, unable to be replaced or repatriated after long tours of duty – unsustainable, both for the safety and well-being of seafarers and the safe operation of ships.

Others who had been on break could not return to work, with dire implications for their personal income. UNCTAD and others have issued calls to designate seafarers and other marine personnel, regardless of nationality, as key workers, and exempt them from travel restrictions,

to ensure that crew changes can be carried out. In addition, temporary guidance was developed for flag States, enabling the extension of the validity of seafarers and ship licences and certificates under mandatory instruments of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and the International Labour Organization.

Sustainable shipping, decarbonization and ship pollution control remain priorities

More stringent environmental requirements continue to shape the maritime transport sector. Carriers need to maintain service levels and reduce costs, and at the same time ensure sustainability in operations. Greenhouse gas emissions from international shipping continue to rank high on the international policy agenda.

Progress was made at IMO towards the ambition set out in its initial strategy on reduction of greenhouse gas emissions from ships. These include ship energy efficiency, alternative fuels and the development of national action plans to address greenhouse gas emissions from international shipping.The increase in vessel size, combined with multiple efficiency gains and the recycling of less efficient vessels, have constrained growth in carbon dioxide emissions, despite growth in total fleet tonnage.

Some further gains can reasonably be expected over the next decade, as modern eco-designs continue to replace older and less efficient ships. However, these marginal improvements will not be sufficient to meaningfully decrease overall carbon-dioxide emissions as specified in the IMO target of reducing total annual greenhouse gas emissions by at least 50 per cent by 2050 compared with levels in 2008.

Achieving these targets will require radical engine and fuel technology changes.With regard to the protection of the marine environment and the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity, there are several areas where regulatory action has recently been taken or is under way. These include the implementation of the IMO 2020 sulphur limit, ballast-water management, measures to address biofouling, the reduction of pollution from plastics and microplastics, safety considerations of new fuel blends and alternative marine fuels, and the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction.

The implementation of the IMO sulphur cap regulation as of 1 January 2020 had been considered relatively smooth at the outset. However, difficulties arose in relation to disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. In March 2020, the ban on the carriage of non-compliant fuel oil entered into force to support the implementation of the sulphur cap. Its enforcement by port State control authorities was limited, due to measures put in place to reduce the number of inspections and contain the risk of spreading the coronavirus. It will be important to ensure

that any delay will not have a negative impact on the long-term implementation of the sulphur cap regulatiotion